OPOD - Greenland Halos

OPOD - Greenland Halos: A Mesmerizing Display of Atmospheric Optics

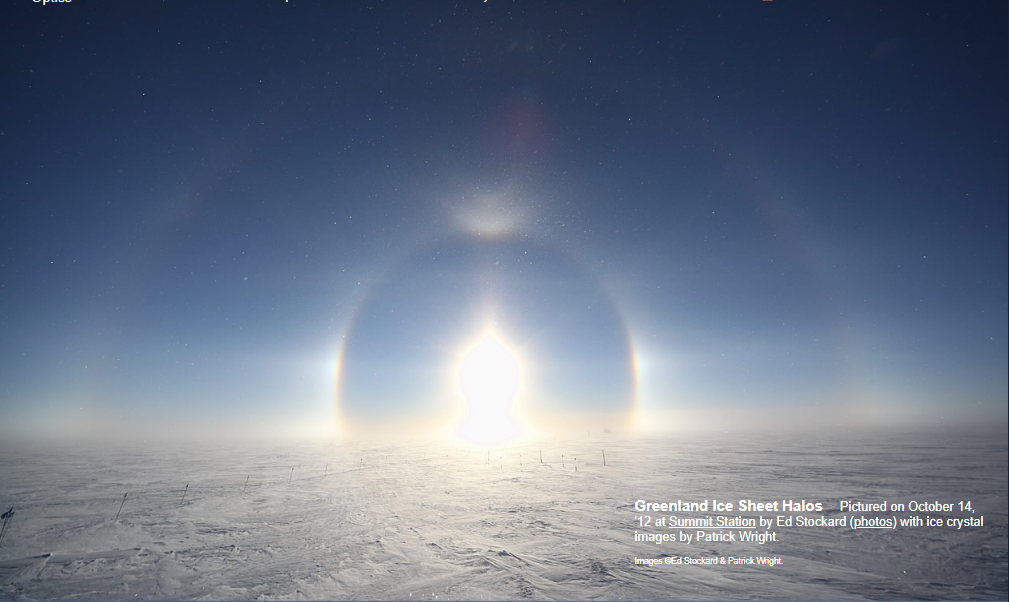

Greenland, known for its vast ice sheet, offers a stunning backdrop for observing atmospheric optics phenomena. On October 14, '12, Ed Stockard captured mesmerizing images of halos formed by ice crystals at Summit Station. Accompanied by Patrick Wright's close-up shots of diamond dust crystals, these photographs provide a rare glimpse into the beauty of these natural optical phenomena.

Despite challenging shooting conditions, with temperatures plummeting to -27°C and winds blowing at 14-15 knots straight on, Stockard and Wright persevered to capture the captivating spectacle. Stockard's eyelashes froze together, his glasses fogged up rapidly, and his cheeks and forehead felt frost nipped even with protective gear. However, these obstacles did not deter them from documenting the breathtaking Greenland halos.

To capture the surface halo photos, Stockard employed a technique taught by Marko Riikonen. He took a picture and then side-stepped to repeat the process multiple times. Unfortunately, the snowy surface had a crust that broke under each step, making it challenging to maintain a steady flow and hold his breath for the perfect shot. Eventually, Stockard had to abandon this method due to the difficulties it posed.

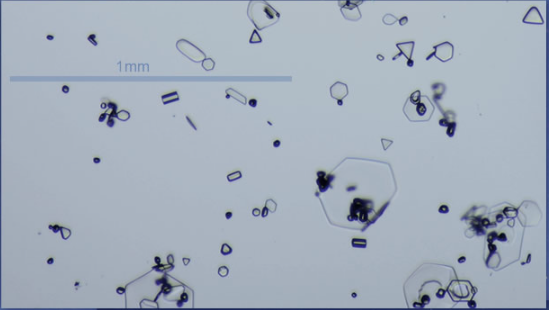

Meanwhile, Wright used a camera mounted onto a microscope, following the instructions detailed on snowcrystals.com. Holding glass slides as perpendicular to the wind as possible, he allowed the diamond dust to hit and adhere to the slides. To combat the freezing temperatures, Wright carried hand warmers in his pockets, switching them between his hands to keep warm. Jennie Mowatt, another member of their team, ingeniously suggested holding the slide up in the air against the wind, simplifying the process and allowing for better crystal capture.

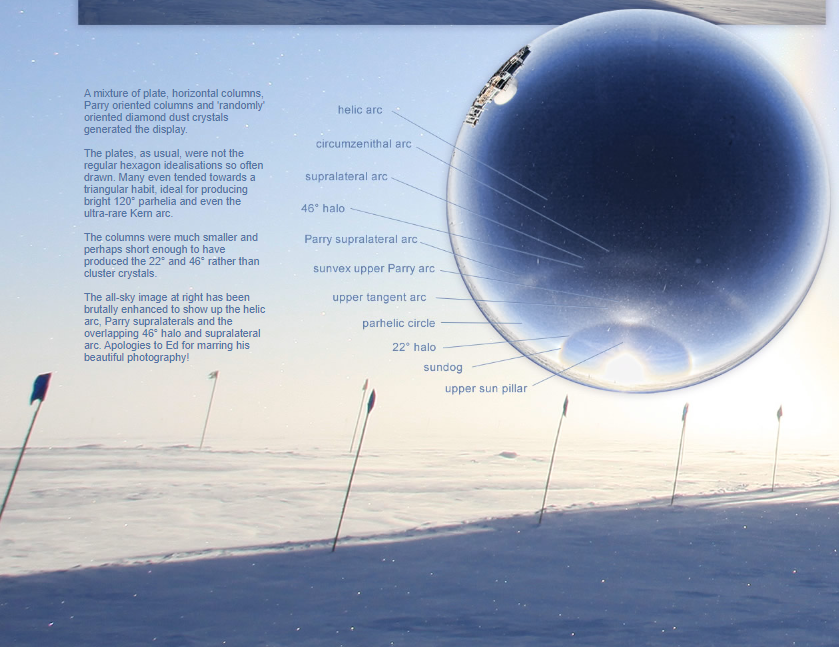

The Greenland halos observed in these images are a result of a mixture of different ice crystal shapes, including plates, horizontal columns, Parry oriented columns, and randomly oriented diamond dust crystals. The plates, deviating from the regular hexagonal shape typically depicted, often exhibited a triangular habit, which is conducive to generating bright 120° parhelia and even the rare Kern arc. The columns observed were smaller and possibly short enough to produce the 22° and 46° halos.

In one of the all-sky images, enhanced to highlight specific features, the helic arc, Parry supralaterals, and the overlapping 46° halo and supralateral arc can be seen. Although this enhancement slightly affects the original beauty of Stockard's photography, it allows for a clearer understanding of the various atmospheric optical phenomena present in the scene.

The Greenland halos showcased in these photographs are a testament to the awe-inspiring wonders of atmospheric optics. The intricate interplay between ice crystal shapes and sunlight creates a visual spectacle that captivates both scientists and nature enthusiasts alike. These fleeting moments of optical beauty serve as a reminder of the complexity and diversity found in our atmosphere.

Please note that this article has been automatically converted from the old site and may not appear as intended. To view the original article, visit the provided link.

In conclusion, Greenland halos offer a breathtaking display of atmospheric optics, showcasing the unique beauty created by ice crystals interacting with sunlight. Despite challenging shooting conditions, photographers like Ed Stockard and Patrick Wright have managed to capture these stunning phenomena, providing invaluable insights into the intricacies of our atmosphere. By sharing these images, we can appreciate the wonders of nature and gain a deeper understanding of the mesmerizing world of atmospheric optics.

Greenland Ice Sheet Halos ~ Pictured on October 14, '12 at Summit Station by Ed Stockard (photos) with ice crystal images by Patrick Wright.

Images ©Ed Stockard & Patrick Wright.

"Today was the first day in quite some time that we have had significant sky optics. A remarkable part to the episode is that I was able to get these photos while Patrick was able to get some great shots of the actual diamond dust .crystals..

Shooting conditions were actually quite poor. Wind and diamond dust was blowing right toward the camera. My eyelashes were freezing together and my glasses fogged up quickly. Temps were -27C and winds 14-15knots straight on. Despite a balaclava and heavy pile hat and neck gaiter, my cheeks and forehead continually felt like they were frost nipped. The sun blocker would touch my cheek as well and I finally removed that. I tried to take surface halo photos as Marko .Riikonen. had taught me.... take a pic and side step and repeat, repeat, repeat. There was a crust on the snow and I would break through on each step probably about 15cm or more and I couldn't maintain a good flow and hold my breath for a photo. I gave up with that pretty quickly.

Patrick said he took about a hundred diamond dust photos and gave up when his hands couldn't stand it anymore."

"We used a camera mounted onto a microscope, exactly as described in snowcrystals.com . I simply held glass slides up as perpendicular to the wind as I could, and the diamond dust would hit the slide and stick....there may be minor melting from heat conducting from my fingers through the slide (slightly rounded edges on some crystals). I had my pockets loaded with hand warmers and would rotate from one hand to the other, holding the slide up in the air as long as I could handle it. I must credit our other science tech Jennie Mowatt - I was trying all these fancy wood blocks and aluminum tubes to try and create a leeward effect to capture the crystals, and she walked up and said "why don't you just hold the slide up in the air against the wind?"

A mixture of plate, horizontal columns, Parry oriented columns and 'randomly' oriented diamond dust crystals generated the display.

The plates, as usual, were not the regular hexagon idealisations so often drawn. Many even tended towards a triangular habit, ideal for producing bright 120° parhelia and even the ultra-rare Kern arc.

The columns were much smaller and perhaps short enough to have produced the 22° and 46° rather than cluster crystals.

The all-sky image at right has been brutally enhanced to show up the helic arc, Parry supralaterals and the overlapping 46° halo and supralateral arc. Apologies to Ed for marring his beautiful photography!

Note: this article has been automatically converted from the old site and may not appear as intended. You can find the original article here.

Reference Atmospheric Optics

If you use any of the definitions, information, or data presented on Atmospheric Optics, please copy the link or reference below to properly credit us as the reference source. Thank you!

-

<a href="https://atoptics.co.uk/blog/opod-greenland-halos-2/">OPOD - Greenland Halos</a>

-

"OPOD - Greenland Halos". Atmospheric Optics. Accessed on November 26, 2024. https://atoptics.co.uk/blog/opod-greenland-halos-2/.

-

"OPOD - Greenland Halos". Atmospheric Optics, https://atoptics.co.uk/blog/opod-greenland-halos-2/. Accessed 26 November, 2024

-

OPOD - Greenland Halos. Atmospheric Optics. Retrieved from https://atoptics.co.uk/blog/opod-greenland-halos-2/.