Kingfisher Colours - OPOD

Kingfisher Colours - OPOD: A Closer Look at the Optical Engineering Behind the Vibrant Hues

When we catch a glimpse of a kingfisher, its stunning turquoise blue wings and vibrant orange breast immediately grab our attention. These captivating colors are not simply the result of pigments but rather the product of remarkable optical engineering. In this article, we will delve deeper into the fascinating world of kingfisher colors, exploring the intricate mechanisms that create these eye-catching hues.

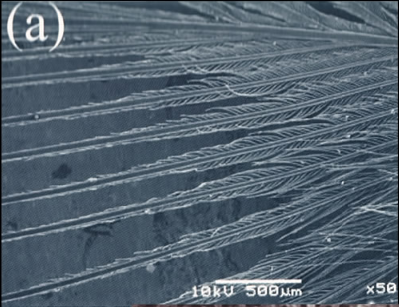

The vivid orange feathers of the kingfisher's breast are reminiscent of hues found in an artist's paint box. These feathers contain small grains of pigment, which contribute to their vibrant appearance. However, it is the blue wings and tail of the kingfisher that truly captivate our imagination. Surprisingly, these feathers do not contain any pigments. Instead, electron microscopy reveals a different structure within their feather barbs - a transparent spongy keratin structure surrounded by a thin cuticle.

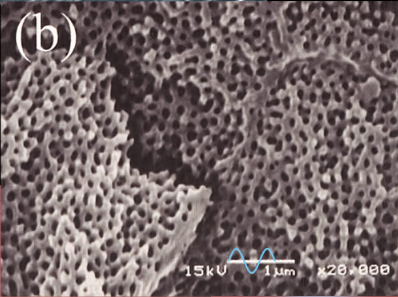

At first glance, the spongy structure appears random in form and dimension. However, upon closer examination, mathematic analysis using a 2D Fourier Transform uncovers a quasi-periodicity in the spacing of the sponge. For the kingfisher's back feathers, this characteristic length is approximately 211 nanometers. The interaction between light waves scattered across the sponge enhances blue and green wavelengths, resulting in the stunning blue coloration we observe.

Interestingly, the tail feathers of the kingfisher possess a slightly smaller sponge dimension of approximately 187 nanometers. As a result, these feathers exhibit a deeper and shorter wavelength blue coloration. To further confirm the role of the sponge in producing these vibrant hues, microscopists filled it with xylene, a substance with a refractive index similar to that of the sponge backbone. As expected, the blue color vanished when the sponge was filled with xylene.

Let's take a closer look at the structure of the kingfisher feathers. Only the barbs of the feathers are filled with the spongy structure responsible for the coloration. This keratin structure contains air-filled holes, which contribute to the wavelength selective iridescence observed in the feathers. The spacing of these holes exhibits a pseudo order, further enhancing the optical properties of the feathers.

In order to better understand the science behind kingfisher colors, scientists have conducted extensive research on structural colors in nature. Professor Shuichi Kinoshita and Professor Shinya Yoshioka, from Osaka University in Japan, have made significant contributions in this field. Their research has shed light on the role of regularity and irregularity in the structure of natural colors. By analyzing the structure of various organisms, including the kingfisher, they have provided valuable insights into the mechanisms behind these stunning hues.

In conclusion, the vibrant colors exhibited by kingfishers are not simply a result of pigments, but rather a remarkable example of optical engineering. The combination of a spongy keratin structure and carefully spaced air-filled holes creates a wavelength selective iridescence that gives rise to the mesmerizing blue and orange hues we associate with these birds. Through the use of advanced microscopy techniques and mathematical analysis, scientists continue to unravel the secrets behind these awe-inspiring colors found in nature. The study of kingfisher colors serves as a reminder of the extraordinary diversity and complexity of the natural world.

Kingfisher Colours ~ A kingfisher imaged near Paris by Denis Joye. The small bird’s iridescent turquoise blue wing and bright orange breast are unmistakable. Its colours are the result of some remarkable optical engineering.

Kingfisher images ©Denis Joye shown with permission

Breast feathers of bright orange are paint box stuff. The feather barbs contain small grains of pigment.

Blue wings and tail are a different matter. They have no pigment. Electron microscopy shows the feather barbs to contain a transparent spongy keratin structure surrounded by few micron thick cuticle.

The sponge generates the colour. At first sight (right) it appears random in form and dimension. It is not. There is order of a sort. Mathematic analysis (2D Fourier Transform) reveals a quasi periodicity in the sponge spacing with a characteristic length for the back feathers of 211 nm. Interference between light waves scattered across the sponge strongly enhances blue and green wavelengths.

Interestingly, the tail feathers have a slightly smaller sponge dimension of 187 nm and indeed, these feathers are a deeper shorter wavelength blue. If more proof be needed of the sponge’s role, microscopists filled it with xylene which has a refractive index close to that of the sponge backbone. The blue colour disappeared.

(a) Kingfisher feather barbs. Only the barbs are sponge filled and coloured.

(b) The sponge. Keratin with air filled holes. The hole spacing has a pseudo order and is responsible for the wavelength selective iridescence.

A 'wave' of kingfisher blue light is shown for reference.

(a) and (b) from Kinoshita S. & Yoshioka S, 'Structural colors in nature:The role of regularity and irregularity in the structure'. Chem Phys Chem 6:1442-1459 (2005).

Reproduced with permission from Professor Shuichi Kinoshita, Osaka Univ., Japan.

Note: this article has been automatically converted from the old site and may not appear as intended. You can find the original article here.

Reference Atmospheric Optics

If you use any of the definitions, information, or data presented on Atmospheric Optics, please copy the link or reference below to properly credit us as the reference source. Thank you!

-

<a href="https://atoptics.co.uk/blog/kingfisher-colours-opod/">Kingfisher Colours - OPOD</a>

-

"Kingfisher Colours - OPOD". Atmospheric Optics. Accessed on December 23, 2024. https://atoptics.co.uk/blog/kingfisher-colours-opod/.

-

"Kingfisher Colours - OPOD". Atmospheric Optics, https://atoptics.co.uk/blog/kingfisher-colours-opod/. Accessed 23 December, 2024

-

Kingfisher Colours - OPOD. Atmospheric Optics. Retrieved from https://atoptics.co.uk/blog/kingfisher-colours-opod/.