Sundog Formation

Sundog Formation: A Phenomenon of Atmospheric Optics

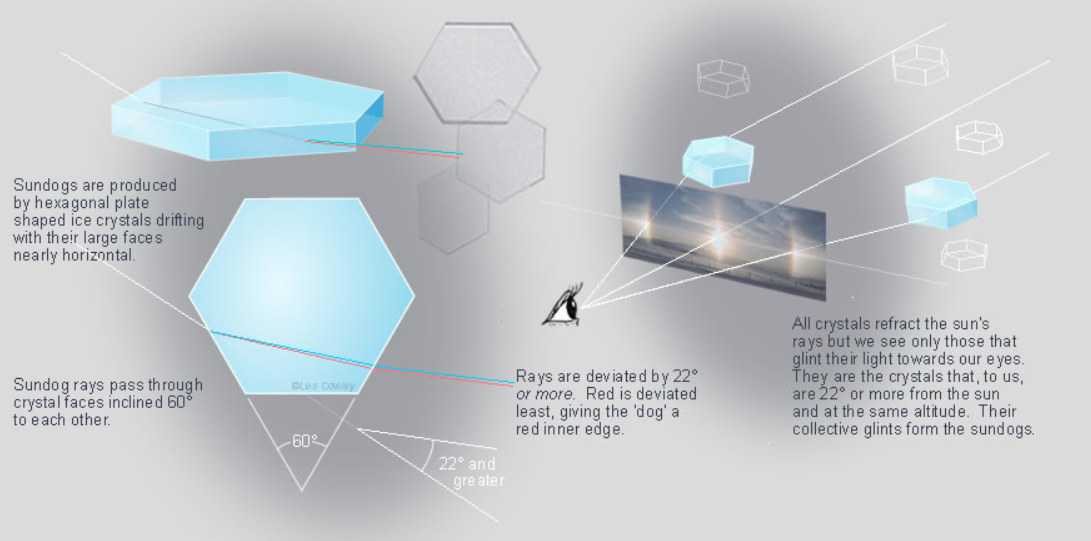

Sundogs, also known as parhelia, are captivating atmospheric optical phenomena that occur worldwide. They are formed by plate crystals found high in cirrus clouds or even at ground level in cold climates, where they are known as diamond dust. These plate crystals gently drift and float downwards, with their large hexagonal faces nearly horizontal.

When rays of sunlight enter a side face of the plate crystal and leave through another inclined face approximately 60° away, the rays contribute their glint to form a sundog. The two refractions deviate the ray by at least 22°, depending on its initial angle of incidence. The minimum deviation of about 22° occurs when the internal ray crossing the crystal is parallel to an adjacent face.

One interesting characteristic of sundogs is their coloration. Red light is refracted less strongly than blue light, resulting in the inner edges of sundogs appearing red. This color difference is due to the varying degrees of refraction experienced by different wavelengths of light.

Plate crystals can also create a variety of other halos when rays pass through them in different ways. The specific arrangement of the crystals and the angles at which the rays interact with them determine the appearance of these halos.

The position of the sun in the sky also plays a role in sundog formation. When the sun is relatively high, rays cannot pass through the crystal unless they are channeled by being internally reflected from the upper and lower basal (large hexagonal) faces. The skewed angle of incidence causes the ray deviation to increase, resulting in sundogs appearing farther from the sun when it is high in the sky.

It is worth noting that plate crystals rarely float exactly horizontal; they wobble as they descend through the atmosphere. The extent of this wobbling increases with crystal size. As a result, wobbly plates can produce tall sundogs. In some cases, the distinction between a tall sundog and fragments of a 22° halo becomes somewhat arbitrary.

To observe sundogs, it is best to look towards the sun at an angle of approximately 22°. Sundogs are often seen as bright spots of light on either side of the sun, forming a halo-like effect. These optical phenomena are most commonly observed in colder climates and during the winter months when cirrus clouds and diamond dust are more prevalent.

In conclusion, sundogs are mesmerizing atmospheric optical phenomena that occur when sunlight interacts with plate crystals in cirrus clouds or diamond dust. The refraction and deviation of rays passing through these crystals create the distinctive appearance of sundogs, with their red-hued inner edges. Understanding the intricacies of sundog formation adds to our appreciation of the beauty and complexity of the natural world.

Sundogs, parhelia, are formed by plate crystals high in the cirrus clouds that occur world-wide. In cold climates the plates can also be in ground level as diamond dust.

The plates drift and float gently downwards with their large hexagonal faces almost horizontal. Rays that eventually contribute their glint to a sundog enter a side face and leave through another inclined 60° to the first. The two refractions deviate the ray by 22° or more depending on the ray's initial angle of incidence when it enters the crystal. The condition where the internal ray crossing the crystal is parallel to an adjacent face gives the minimum deviation of about 22°.

Red light is refracted less strongly than blue and the inner, sunward, edges of sundogs are therefore red hued.

Rays passing through plates crystals in other ways form a variety of halos.

When the sun is relatively high, rays cannot pass through the crystal unless they are channeled by being internally reflected from the upper and lower basal (large hexagonal) faces. The skewed angle of incidence also causes the ray deviation to increase and high sun sundogs are farther from the sun.

Plate crystals rarely float exactly horizontal, they wobble and the wobble increases with crystal size. Wobbly plates produce tall sundogs and in the more extreme cases the distinction between a tall sundog and fragments of a 22° halo becomes somewhat arbitrary.

Note: this article has been automatically converted from the old site and may not appear as intended. You can find the original article here.

Reference Atmospheric Optics

If you use any of the definitions, information, or data presented on Atmospheric Optics, please copy the link or reference below to properly credit us as the reference source. Thank you!

-

<a href="https://atoptics.co.uk/blog/sundog-formation/">Sundog Formation</a>

-

"Sundog Formation". Atmospheric Optics. Accessed on December 3, 2024. https://atoptics.co.uk/blog/sundog-formation/.

-

"Sundog Formation". Atmospheric Optics, https://atoptics.co.uk/blog/sundog-formation/. Accessed 3 December, 2024

-

Sundog Formation. Atmospheric Optics. Retrieved from https://atoptics.co.uk/blog/sundog-formation/.