OPOD - Viking Sunstone

OPOD - Viking Sunstone: Unlocking the Secrets of Ancient Navigation

The Vikings were renowned seafarers, embarking on daring voyages across the treacherous North Atlantic. However, without the aid of modern navigation tools, how did they navigate their way through vast expanses of open water? While there is no direct evidence, some theories suggest that the Vikings may have used a fascinating device known as a sunstone or sun seeker. In this article, we delve into the mysteries of the Viking sunstone and explore how it could have played a crucial role in their maritime exploits.

The Sunstone's Polarized Light: A Guiding Beacon in the Sky

Blue sky, a result of sunlight being scattered by air molecules, holds the key to understanding the workings of the sunstone. Sunlight is preferentially polarized in a specific direction, with the electric vector perpendicular to the sun's rays. By analyzing the polarization of blue skylight, one can determine the direction of the sun. This is where the Iceland Spar, or calcite crystal, comes into play.

The Iceland Spar Crystal: A Marvel of Light Manipulation

The Iceland Spar crystal is a unique device that can split blue skylight into two polarized components. This crystal is highly anisotropic, meaning it behaves differently depending on the direction of light passing through it. When light enters the crystal, it splits into two polarized components that travel in different directions. As a result, objects viewed through the crystal appear doubled.

To utilize the sunstone, one simply needs to place a sticker or a blob of Viking Stockholm tar on the crystal's top face. When viewed through the bottom face, the sticker's image is doubled. By holding the crystal up to the sky and rotating it, one can observe changes in intensity between the two images. When the images are equally dark, a condition that can be judged rather precisely, the crystal's long edges point in the direction of the sun.

Unlocking the Secrets of the Sun: Conditions for Effective Use

For the sunstone to be effective, the sun must be low on the horizon, as is often the case during the Viking era. Additionally, moderately blue sky overhead is necessary for accurate readings. It's important to note that the sun seeker does not work on completely cloudy days, as light from the blue sky beyond the clouds becomes depolarized due to multiple scattering from cloud water droplets.

Testing the Sunstone: A Modern Perspective

While we can only speculate about the Vikings' use of sunstones, we can still test their operation in modern times. On cloudy days, one can examine a white LCD monitor screen, which emits strongly polarized light, through the crystal. As the crystal is rotated, the two images on the screen will change in intensity, providing a practical way to verify the accuracy of the sunstone.

The Viking Sunstone and Arctic Navigation

The North Atlantic and near Arctic waters often presented challenging conditions for Viking navigators. Thin sea fog layers at dawn frequently obstructed sightings of the sunrise position. However, overhead, the sky remained blue. In such scenarios, a sunstone could have utilized the polarized blue sky to determine the direction of the hidden sun. Similarly, towards sunset, when distant clouds often concealed the sun but left some blue sky visible overhead, the sunstone could still function effectively.

The Viking Legacy: Consummate Sailors or Master Navigators?

While the use of sunstones remains speculative, it is undeniable that the Vikings were exceptional sailors. Their ability to navigate vast distances without modern navigational tools is a testament to their skills and knowledge of the natural world. The smells of the air and ocean, the character of waves and winds, and the behavior of birds and sky all provided cues that these seafarers were keenly attuned to. It is possible that the Vikings relied more on their intuition and observations of nature rather than magical devices.

In conclusion, the Viking sunstone remains an intriguing aspect of ancient navigation. Although we may never know for certain if the Vikings used these devices, the concept of using polarized light to determine the sun's direction is a fascinating one. Whether through the aid of sunstones or their own remarkable navigational abilities, the Vikings achieved extraordinary feats that continue to captivate our imagination today.

Viking Sun Stones?

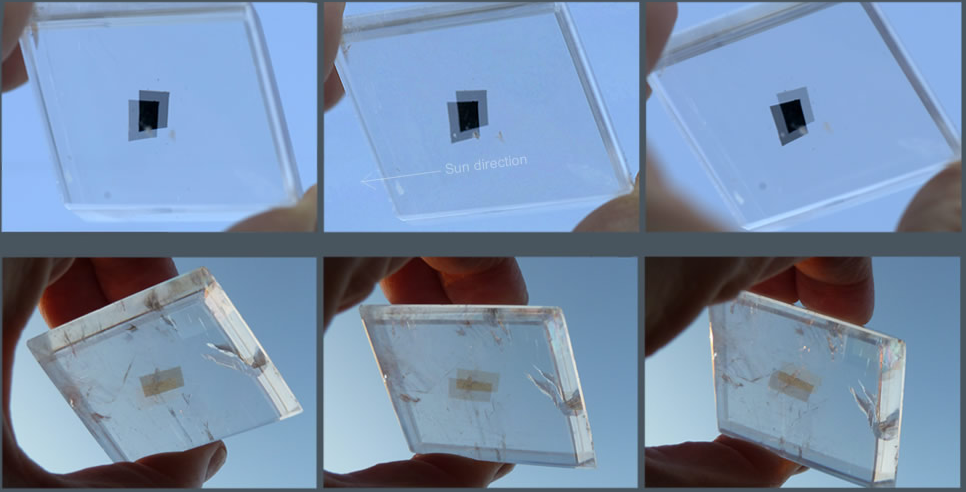

Top row ~ John Stetson finds the direction of the sun using a calcite crystal.

Calcite crystals, Iceland Spar, produce double images. The two black shapes are the doubled shadow of a paper sticker on the crystal upper face. When the two shadows are equally dark the long side of the crystal points to the sun. A sunstone or sun seeker. The sun itself was only 1° high and hidden by trees.

Bottom row ~ Ever the sceptic, Les Cowley also tests a crystal to see if it really seeks the sun. It was remarkably accurate and sensitive, locating the sun direction to within a degree or so. The late afternoon sun was 4° high.

Images ©John Stetson & Les Cowley

Blue sky is a product of sunlight Rayleigh scattered by air molecules. Its light is preferentially polarised with the electric vector perpendicular to the sun's rays and the polarisation is almost complete at 90� from the sun. Analysis of the polarisation gives the sun direction and so any device that splits blue skylight light into two polarised components and compares their intensities can act as a sunstone or sun seeker.

An Iceland Spar, calcite, crystal is just such a device. The crystal, built of arrays of negatively charged carbonate and positive calcium ions, is highly anisotropic. Light entering the crystal splits into two polarised components which travel in different directions. It is 'doubly refracting' and objects viewed through it appear doubled.

Place a paper sticker, or blob of Viking Stockholm tar, on the crystal top face and as seen through the bottom face it is doubled. Hold the crystal to the sky with its upper face level and rotate it to and fro. The two images change in intensity. When they are equally dark - a condition that can be judged rather precisely - the crystal long edges point in the sun's direction.

To be effective the sun must be low - as needed anyway for the Viking horizon board - with moderately blue sky overhead. The sun seeker does not work on completely cloudy days because any light from blue sky beyond them is depolarised by multiple scattering from the cloud water droplets.

Test the operation of a sunstone on cloudy days by looking through it at a white LCD monitor screen (strongly polarised). As the crystal is rotated the two images change in intensity.

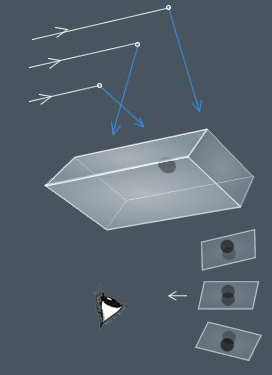

Air molecules scatter blue enriched and polarized light

Calcite crystal with opaque spot on upper face

Spot appears doubled from beneath.

The two spots are equally dark when the crystal long edge points sunward.

North Atlantic Arctic and near Arctic waters often have a thin sea fog layer at dawn. A sighting of the sunrise position is then impossible.

Overhead the sky is blue. A sunstone could use the polarised blue sky to find the sun direction.

Later on the sun breaks through to form a fogbow - but too late for a Viking sun sighting.

Viking sunstone?

Viking sunstone?

21st Century sunstone

21st Century sunstone

The Vikings started to settle in Iceland in the 860-70s. Inhabitable land was eventually taken and the Icelandic Sagas have it that a new land, Greenland, was reconnoitred in the 980s by Eric the Red. Two colonies of 3-4000 people were later established on its western coast. North America was probably first sighted by Bjarni Herjolfsson who, driven off course in 985/6 en route to Greenland from Iceland, reached but did not set foot on land to the west. Erik the Red's son, Leif the Fortunate, made a deliberate voyage westwards in ~1001, crossed the Davis Straight and landed on Baffin Island. He then sailed down the coast of Labrador to Newfoundland where a Viking settlement has been discovered. It is uncertain whether he sailed further south although vines and grapes were said to have been found and the Vikings called the land Vinland. From then on Viking longships regularly sailed back and forth across the Atlantic.

The Vikings were remarkable seafarers. There is no evidence that they had a magnetic compass. With our almost total reliance on advanced electronics and satellites for navigation it is seen as near impossible that Vikings in their small open ships could make such voyages without some navigational device. Their voyages were made in summer and at high latitudes the days were long and the sky did not get completely dark. Celestially, they had to rely on the sun rather than stars.

There is some evidence that they used an horizon board to help find latitude. This had the bearing of the sunrise and sunset marked with peg holes for their home port and a number of dates. To sail due west and reach Iceland and then Greenland they could sight the sun at sunrise and sunset each day and compare it with pegs on the board to set their course west.

However, the North Atlantic especially in Arctic or near Arctic waters is frequently cloud covered or there is a sea fog layer that hides a low sun but irritatingly shows blue sky overhead - thus the need for a sun seeker. On a typical Arctic morning with thin fog hiding sunrise an Iceland Spar sunstone could easily give an accurate bearing. Similarly towards sunset when distant clouds often hide the sun but leave some blue sky overhead the sunstone also works. And Iceland Spar crystals could be found on the ground in Iceland.

This is speculation, there is no direct evidence that they used sunstones. Less exciting perhaps, they were simply consummate sailors. The smells of the air and of the ocean, the character of the waves and winds, birds and moods of the sky were all cues that they were likely very sensitive to. They perchance had little need of magical devices.

Many thanks to John Stetson for alerting OPOD to sunstones.

Note: this article has been automatically converted from the old site and may not appear as intended. You can find the original article here.

Reference Atmospheric Optics

If you use any of the definitions, information, or data presented on Atmospheric Optics, please copy the link or reference below to properly credit us as the reference source. Thank you!

-

<a href="https://atoptics.co.uk/blog/opod-viking-sunstone/">OPOD - Viking Sunstone</a>

-

"OPOD - Viking Sunstone". Atmospheric Optics. Accessed on December 20, 2024. https://atoptics.co.uk/blog/opod-viking-sunstone/.

-

"OPOD - Viking Sunstone". Atmospheric Optics, https://atoptics.co.uk/blog/opod-viking-sunstone/. Accessed 20 December, 2024

-

OPOD - Viking Sunstone. Atmospheric Optics. Retrieved from https://atoptics.co.uk/blog/opod-viking-sunstone/.