OPOD - Below Horizon Halos

OPOD - Below Horizon Halos: A Fascinating Phenomenon

Have you ever gazed at the sky and been captivated by the beauty of atmospheric optics? One such captivating phenomenon is the occurrence of below horizon halos, specifically subsuns and subparhelia. These mesmerizing optical illusions can be observed when the sun is below the horizon, creating a stunning display of light and color. In this article, we will delve deeper into the science behind these below horizon halos and explore their formation.

Subsun: A Dazzling Mirror Image

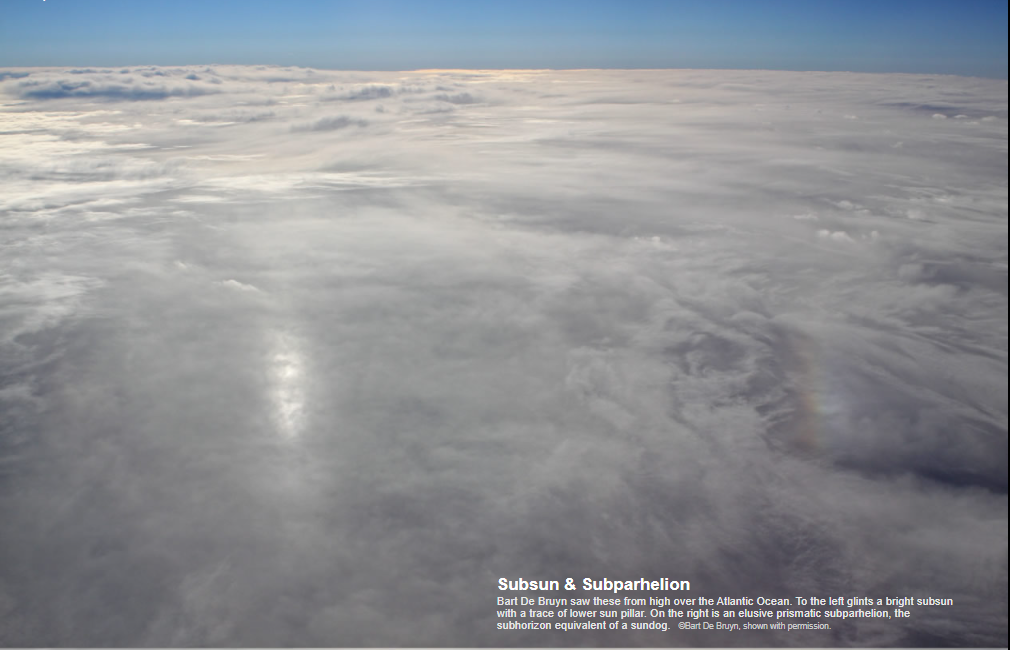

One of the most striking below horizon halos is the subsun. This ethereal spectacle can be seen in clouds directly beneath the sun and an equal distance below the horizon. The subsun is formed by plate crystals, which are large hexagonal ice crystals with almost horizontal faces. These crystals reflect sunlight back upwards, creating a mirror image of the sun below the horizon. The subsun can appear blindingly bright and is often accompanied by a faint lower sun pillar.

Subparhelion: The Subhorizon Sundog

On the right side of the above image, you can spot an elusive subparhelion. Considered as the subhorizon equivalent of a sundog, the subparhelion adds an extra touch of wonder to the atmospheric display. The subparhelion is formed by plate crystals as well, but its formation involves multiple internal reflections of sunlight. Rays of light pass between two inclined plate crystal side faces, with most ray paths being more complex. These rays are internally reflected multiple times between two large horizontal faces before emerging from the crystal.

The Role of Internal Reflections

The key to understanding the formation of both subsuns and subparhelia lies in internal reflections within plate crystals. When sunlight encounters these hexagonal ice crystals, it undergoes a series of internal reflections before escaping. In the case of a sundog, an even number of internal reflections occurs, resulting in a familiar halo above the horizon. However, when an odd number of internal reflections takes place, a subparhelion is formed below the horizon, typically around 22 degrees or more from the subsun.

Exploring the Complexity

While the concept of subsuns and subparhelia may seem straightforward, the actual paths of light within the plate crystals can be quite complex. Light can be internally reflected twice or more between the two large horizontal faces of the crystal before finally emerging. The intricate interplay between these internal reflections gives rise to the captivating and ever-changing patterns observed in below horizon halos. Each display is unique, offering a glimpse into the mesmerizing complexity of atmospheric optics.

Observing Below Horizon Halos

To witness the enchanting beauty of subsuns and subparhelia, one must be in the right place at the right time. These below horizon halos are most commonly observed from high vantage points, such as on an airplane flying over clouds or from elevated locations overlooking expansive bodies of water. The clear skies and unobstructed views afforded by these locations enhance the chances of spotting these rare atmospheric phenomena.

Conclusion

In conclusion, below horizon halos, including subsuns and subparhelia, are awe-inspiring manifestations of atmospheric optics. The interplay between plate crystals and internal reflections gives rise to these captivating displays of light and color. While subsuns mirror the sun directly beneath the horizon, subparhelia add an extra touch of wonder as subhorizon sundogs. Observing these below horizon halos provides a glimpse into the intricacies of light's journey through ice crystals, showcasing the beauty and complexity of our atmosphere. So, keep your eyes to the sky and be prepared to witness nature's breathtaking spectacle unfold before you.

Subsun & Subparhelion

Bart De Bruyn saw these from high over the Atlantic Ocean. To the left glints a bright subsun with a trace of lower sun pillar. On the right is an elusive prismatic subparhelion, the subhorizon equivalent of a sundog. ©Bart De Bruyn, shown with permission.

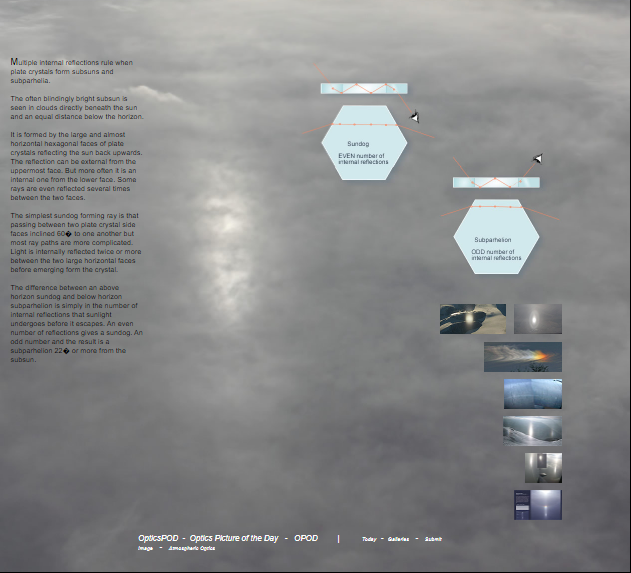

Multiple internal reflections rule when plate crystals form subsuns and subparhelia.

The often blindingly bright subsun is seen in clouds directly beneath the sun and an equal distance below the horizon.

It is formed by the large and almost horizontal hexagonal faces of plate crystals reflecting the sun back upwards. The reflection can be external from the uppermost face. But more often it is an internal one from the lower face. Some rays are even reflected several times between the two faces.

The simplest sundog forming ray is that passing between two plate crystal side faces inclined 60� to one another but most ray paths are more complicated. Light is internally reflected twice or more between the two large horizontal faces before emerging form the crystal.

The difference between an above horizon sundog and below horizon subparhelion is simply in the number of internal reflections that sunlight undergoes before it escapes. An even number of reflections gives a sundog. An odd number and the result is a subparhelion 22� or more from the subsun.

Note: this article has been automatically converted from the old site and may not appear as intended. You can find the original article here.

Reference Atmospheric Optics

If you use any of the definitions, information, or data presented on Atmospheric Optics, please copy the link or reference below to properly credit us as the reference source. Thank you!

-

<a href="https://atoptics.co.uk/blog/opod-below-horizon-halos/">OPOD - Below Horizon Halos</a>

-

"OPOD - Below Horizon Halos". Atmospheric Optics. Accessed on November 12, 2024. https://atoptics.co.uk/blog/opod-below-horizon-halos/.

-

"OPOD - Below Horizon Halos". Atmospheric Optics, https://atoptics.co.uk/blog/opod-below-horizon-halos/. Accessed 12 November, 2024

-

OPOD - Below Horizon Halos. Atmospheric Optics. Retrieved from https://atoptics.co.uk/blog/opod-below-horizon-halos/.