Stockholm 1535 halos

Stockholm 1535 Halos: A Closer Look at the Sundog Painting

In the Storkyrkan, Stockholm Cathedral, there is a famous painting called the Vädersolstavlan, also known as the "Sundog painting." This artwork depicts an extraordinary atmospheric phenomenon that occurred over Stockholm on April 20, 1535. It is considered one of the earliest recorded images of the medieval city and has sparked much controversy and fascination over the years.

The painting, created in 1636 as a copy of the original artwork by Urban Mälare, was commissioned by Bishop Olaus Petri. The depiction of the sky events, particularly the presence of "six suns," became a subject of dispute between the church and the elected King of Sweden Gustav Vasa. Despite the controversy, the painting accurately portrays the halo display that was witnessed on that fateful day.

Interestingly, the artist chose to depict the sky not as it would be seen with the naked eye but rather through the lens of a modern fish-eye lens. The entire sky is shown in an azimuthal or possibly a stereographic projection, which is quite different from how Stockholm and the landscape are portrayed. The halo shapes in the painting are represented by arcs of circles, a convention that persisted long after the creation of this artwork.

Let's take a closer look at the different elements depicted in the Sundog painting and how they compare to modern simulations:

-

Parhelic Circle: The painting prominently features a bright and complete parhelic circle, with the sun placed at the upper right. A simulation using HaloSim software confirms that this depiction aligns with what would be expected. The parhelic circle is formed by sunlight reflecting off ice crystals in the atmosphere.

-

Sundogs: Close to the sun in the painting, two "extra suns" or sundogs are shown. These sundogs are caused by plate-oriented ice crystals. The simulation also confirms the presence of these sundogs, further validating the accuracy of the painting.

-

120° Parhelia: Two additional sun-like brightenings, known as 120° parhelia, are depicted in the painting. These are also caused by plate crystals and are positioned near the sundogs. The simulation confirms their presence in the sky.

-

Anthelion: Opposite the sun in the painting, there is another brightening. This is not a true halo but rather an area where Wegener arcs from column crystals intersect the parhelic circle. The simulation also captures this feature, adding to the accuracy of the painting.

-

22° Halo: The painting's representation of the 22° halo appears to be slightly off-center. This could be due to following a stereographic projection while using circles to depict the arcs. Nonetheless, the presence of the 22° halo in the painting indicates that column crystals were abundant in the sky that day.

-

Gull-Wing Arcs: Two outer arcs stretching from the 22° parhelia and intersecting above the sun are stylized in the painting. When viewed with half-closed eyes, these arcs resemble the "gull-wing" top of the circumscribed halo seen in simulations. This suggests the prevalence of column crystals during the atmospheric event.

-

Infralateral Arc: At lower left in the painting, there is a large arc that could represent an infralateral arc caused by short horizontal columns. While its position is approximately correct, it does not cross the parhelic circle.

-

Zenith Object: At the zenith, the center of the parhelic circle, there is a problematic object in the painting. It has been commonly referred to as a crescent moon, but historical records indicate that the moon was not in a crescent phase on April 20, 1535. It could potentially be a circumzenithal arc caused by plate crystals, but its depiction does not align with the other arcs in terms of the sun's position and time of day.

The Sundog painting is a testament to the artist's originality, keen observation, and attention to detail. It provides valuable insights into the atmospheric optics phenomenon witnessed over Stockholm in 1535. Despite some minor deviations from reality, the painting accurately captures the essence of the halo display and serves as an important historical record.

For those interested in delving deeper into the Vädersolstavlan and its various aspects, a comprehensive article by Mats Halldin offers further insights and analysis.

In conclusion, the Sundog painting from Stockholm in 1535 is a remarkable piece of art that captures an extraordinary atmospheric optics event. Its accuracy in depicting the halo display and the presence of multiple sun-like phenomena demonstrates the artist's astute observations and attention to detail. This artwork continues to intrigue scientists, historians, and art enthusiasts alike, providing a glimpse into the fascinating world of atmospheric optics in the past.

1535, Stockholm, Sweden

1535, Stockholm, Sweden

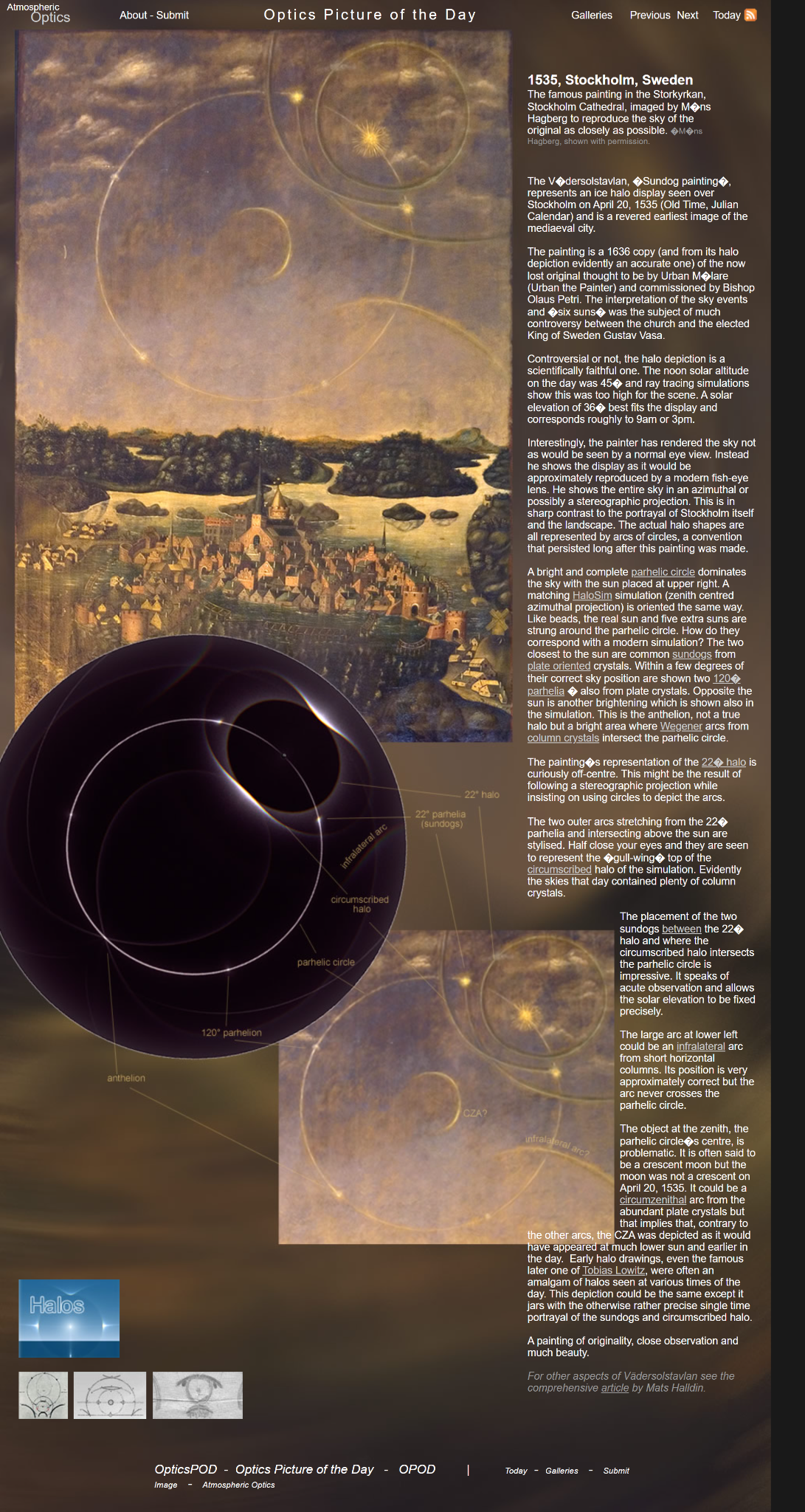

The famous painting in the Storkyrkan, Stockholm Cathedral, imaged by M�ns Hagberg to reproduce the sky of the original as closely as possible. �M�ns Hagberg, shown with permission.

The V�dersolstavlan, �Sundog painting�, represents an ice halo display seen over Stockholm on April 20, 1535 (Old Time, Julian Calendar) and is a revered earliest image of the mediaeval city.

The painting is a 1636 copy (and from its halo depiction evidently an accurate one) of the now lost original thought to be by Urban M�lare (Urban the Painter) and commissioned by Bishop Olaus Petri. The interpretation of the sky events and �six suns� was the subject of much controversy between the church and the elected King of Sweden Gustav Vasa.

Controversial or not, the halo depiction is a scientifically faithful one. The noon solar altitude on the day was 45� and ray tracing simulations show this was too high for the scene. A solar elevation of 36� best fits the display and corresponds roughly to 9am or 3pm.

Interestingly, the painter has rendered the sky not as would be seen by a normal eye view. Instead he shows the display as it would be approximately reproduced by a modern fish-eye lens. He shows the entire sky in an azimuthal or possibly a stereographic projection. This is in sharp contrast to the portrayal of Stockholm itself and the landscape. The actual halo shapes are all represented by arcs of circles, a convention that persisted long after this painting was made.

A bright and complete parhelic circle dominates the sky with the sun placed at upper right. A matching HaloSim simulation (zenith centred azimuthal projection) is oriented the same way. Like beads, the real sun and five extra suns are strung around the parhelic circle. How do they correspond with a modern simulation? The two closest to the sun are common sundogs from plate oriented crystals. Within a few degrees of their correct sky position are shown two 120� parhelia � also from plate crystals. Opposite the sun is another brightening which is shown also in the simulation. This is the anthelion, not a true halo but a bright area where Wegener arcs from column crystals intersect the parhelic circle.

The painting�s representation of the 22� halo is curiously off-centre. This might be the result of following a stereographic projection while insisting on using circles to depict the arcs.

The two outer arcs stretching from the 22� parhelia and intersecting above the sun are stylised. Half close your eyes and they are seen to represent the �gull-wing� top of the circumscribed halo of the simulation. Evidently the skies that day contained plenty of column crystals.

The placement of the two sundogs between the 22� halo and where the circumscribed halo intersects the parhelic circle is impressive. It speaks of acute observation and allows the solar elevation to be fixed precisely.

The large arc at lower left could be an infralateral arc from short horizontal columns. Its position is very approximately correct but the arc never crosses the parhelic circle.

The object at the zenith, the parhelic circle�s centre, is problematic. It is often said to be a crescent moon but the moon was not a crescent on April 20, 1535. It could be a circumzenithal arc from the abundant plate crystals but that implies that, contrary to the other arcs, the CZA was depicted as it would have appeared at much lower sun and earlier in the day. Early halo drawings, even the famous later one of Tobias Lowitz, were often an amalgam of halos seen at various times of the day. This depiction could be the same except it jars with the otherwise rather precise single time portrayal of the sundogs and circumscribed halo.

A painting of originality, close observation and much beauty.

For other aspects of Vädersolstavlan see the comprehensive article by Mats Halldin.

Note: this article has been automatically converted from the old site and may not appear as intended. You can find the original article here.

Reference Atmospheric Optics

If you use any of the definitions, information, or data presented on Atmospheric Optics, please copy the link or reference below to properly credit us as the reference source. Thank you!

-

<a href="https://atoptics.co.uk/blog/stockholm-1535-halos/">Stockholm 1535 halos</a>

-

"Stockholm 1535 halos". Atmospheric Optics. Accessed on December 23, 2024. https://atoptics.co.uk/blog/stockholm-1535-halos/.

-

"Stockholm 1535 halos". Atmospheric Optics, https://atoptics.co.uk/blog/stockholm-1535-halos/. Accessed 23 December, 2024

-

Stockholm 1535 halos. Atmospheric Optics. Retrieved from https://atoptics.co.uk/blog/stockholm-1535-halos/.